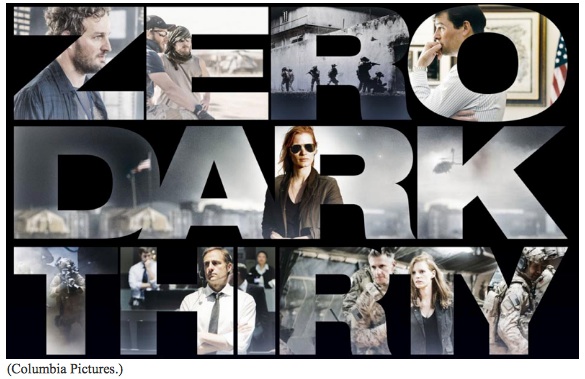

To those critics of Zero Dark Thirty who claim the film misleads the public on the role that waterboarding and other torture played in the hunt for Osama bin Laden, I suggest they look forward to the making of some other film that represents their ideals rather than make Zero Dark Thirty their scapegoat for the mistakes of American policy makers during the War on Terror. Yes, the use of waterboarding and other means of torture (I will not here legitimize the misleading euphemism "enhanced interrogation techniques") are to be condemned. But we should not be so quick to hoist our moral indignation onto a fictional film that was in the works long before the circulation of information regarding the interrogation techniques that decisively led to the discovery of Osama bin Laden in Abbottabad, Pakistan.

The parties responsible for the discrepancies between the film Zero Dark Thirty and the facts of the real interrogations are not the film's screenwriter and director. They are the Bush and Obama administrations, the CIA, and the various incarnations of the Senate Intelligence Committee which have issued conflicting information concerning the interrogation methods of the intelligence officials while withholding strategic data that could have steered the film's makers toward a more accurate account of official interrogation policy and methods. Of course secrecy must be accorded any national security issue, especially one as imperative as the hunt for Osama bin Laden. But such withholding of strategic information also ignites the imaginations of artists engaged in making fictional art and entertainment, and it is entirely hypocritical for senators to come forward with accusations about the deficiencies of a work of art when they themselves have seen to it that such deficiencies would result. Even when considering the last year's disclosures on the kinds of interrogations that proved most productive in the war on terror, the public's knowledge of the facts as they are represented in recent media reports and on the internet regarding how the CIA came by the information leading to bin Laden's whereabouts are still obscure and contradictory. With the history of the Bush-era interrogations particularly murky, the Senate Intelligence Committee and the journalists siding with them appear to be shucking the responsibility that is theirs for any misinformation that entered the public discourse, including the arts, between 2001-08.

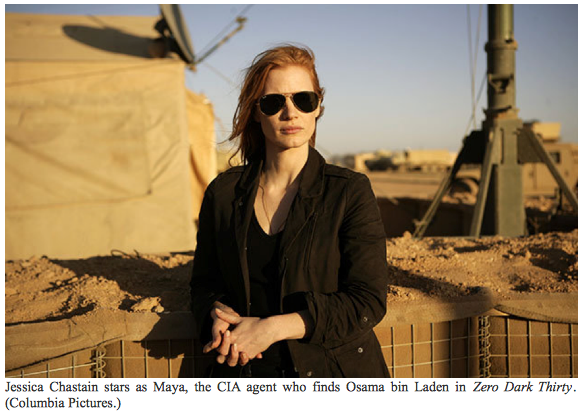

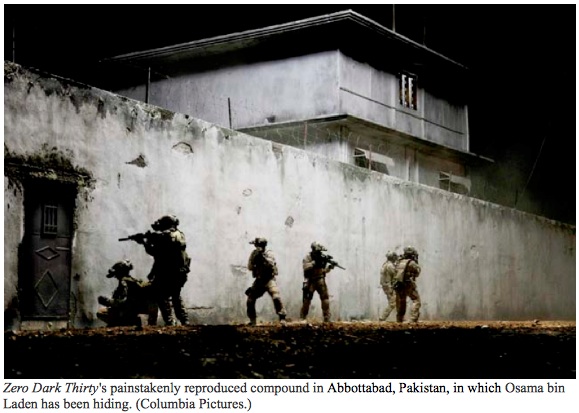

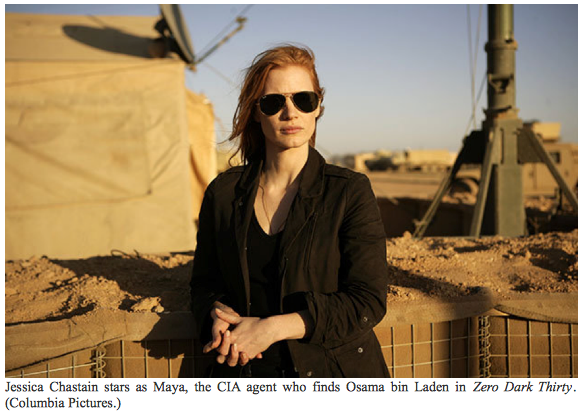

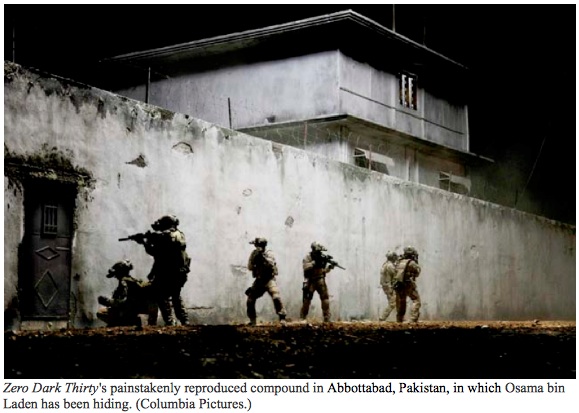

It's true that Zero Dark Thirty's director, Katherine Bigelow, and it's screenwriter, Mark Boal (both of whom are also the film's producers), oversimplified the depictions of torture in relationship to less coercive and physically abusive techniques available to interrogators. But for the filmmakers not to have done so would have mired the film in even more conflicting and divisive ethics and politics, the kind that keep liberals and conservatives in Congress at a perpetual standoff and leaving the more salient issues of the film from ever having gotten off the ground with the choppers carrying the actors playing Navy Seals to their simulated Abbottabad set. In fact, the filmmakers' best defense is that the film is not a simulated documentary, not even a docudrama, in the usual sense that a docudrama follows the facts, however liberally. Zero Dark Thirty cannot be a docudrama in the strictest sense for the simple reason that the facts required for clarity are still not known outside the coterie of intelligence officials and interrogators, senators, and the Bush and Obama administrators who have direct knowledge of the pertinent information regarding the deployment of antiterrorist measures over the last twelve years.

It is this severe deficiency of facts about the war on terror that makes the fictionalization in Zero Dark Thirty not only defensible, but necessary to fill the voids that any fictional account attempts to make. The sheer paucity and inconsistency of facts released by American policy makers, combined with the late timing of those facts that have been released, seems to have escaped the notice of the most impassioned and otherwise well-informed critics of the film, director Alex Gibney, The New Yorker's Jane Mayer, and CNN.com's Peter Bergen. The same void of information appears to escape U.S. Senators Dianne Feinstein (D-Calif.), Carl Levin (D-Mich.), and John McCain (R-Ariz.), who together represent the Senate Intelligence Committee that last week took a hard stand against Zero Dark Thirty and Columbia Pictures for its "misleading" depiction of information obtained from captured Al Qaeda operatives as the result of waterboarding and other means of humiliation and torture. Gibney in particular wrote a seemingly devastating commentary on Alternet that was republished both by Slate.com and Huffington Post, in which he charges the makers of Zero Dark Thirty as being indefensible for having created the false impression that the CIA was led to Osama bin Laden by such illicit means as waterboarding.

The problem with such charges is that the critics leveling them, and especially the Senate Intelligence Committee that seems to be chief among their sources, are altogether better informed than Bigelow and Boal could have been when writing and filming proceed as far back as a 2010, and again when the filmmakers had to be update their filming upon receiving the news of the Abbottabad raid in May 2011. Mayer, Bergen and Gibney in fact base their criticism on details released by the Senate Intelligence Committee's study of the CIA's Detention and Interrogation Program, which entailed more than six million pages of records from the Intelligence Community--presumably most of which were available to Bigelow and Boal at the time they began filming.

Gibney becomes particularly unrealistic when he writes of his disappointment that Bigelow and Boal did not endow the film with the kind of breadth and depth of a George Bernard Shaw drama. "Shaw once said that an argument between a right and a wrong is melodrama," Gibney astutely recalls, "but that an argument between two rights is drama." He then goes on to deduce that when "it came to the subject of torture in?Zero Dark Thirty, there was no argument at all. And so a great dramatic opportunity was missed."

Since Gibney proclaims Bigelow and Boal to be "irresponsible," he might benefit from considering one prominent definition of responsibility during wartime shared by Jean-Paul Sartre and Albert Camus. Among the few views the two Existentialists shared is that which holds human responsibility to be conditioned upon knowledge of one's own limits. We have to know our limits to know what we as individuals are responsible for, and thereby to be free. It follows that in not knowing the limits of the interrogators use of torture, Bigelow and Boal as artists are not only acting responsibly in their fictitious shading in of the empty spaces between known CIA activities and the fragmented information released officially by both the Bush and the Obama administrations, they are also made more responsible by representing the Bush and Obama administrations precisely as those administrations had wished to be perceived by the public at the time of their press conferences. This translates into American policy on coercive interrogation methods being decidedly waterboarding under Bush-Cheney, and famously anti-waterboarding under Obama-Biden.

If we hold to Sartre's and Camus' standard of the limits of knowledge determining our responsibility in action and in art, then the limits to Bigelow and Boal's knowledge regarding the use of torture can be seen as severely restricted by the Presidential administrations and the intelligence community, at least if Bigelow and Boal are telling us the truth that they received no classified information regarding the details of the search and the alleged bagging of bin Laden. As for the film's introductory statement that Zero Dark Thirty is based on first hand accounts, until we know whose accounts they were, we have plenty of reason to believe that that someone willing to talk to Boal (such as the Pentagon's Michael Vickers, or the still-nameless Navy Seal reputed to have made disclosures about the mission) saw the torture being conducted by the CIA under the auspicies of Bush-Cheney-Rumsfeld to be advantageous, if not directly leading to essential disclosure of names and locations. We should be very concerned with this likelihood, as it suggests that the official reports being released by the Senate Intelligence Committee of late may not be entirely accurate.

Peter Bergen wrote that the filmmakers don't "address the fact that eight months ago, the chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee had publicly stated that, based on an exhaustive investigation, there was no evidence that coercive interrogations helped lead to bin Laden's courier." But Bergen apparently doesn't take into account that eight months ago Zero Dark Thirty was already well into post-production before the results of the Committee's exhaustive study had been released, which means it was written a year and more before, as the study was being conducted. Bergen also doesn't seem to take into consideration how the official story on torture shifted within the Bush administration as public dissent was voiced against the waterboarding defended by Secretary Rumsfeld and Vice President Cheney, and of course the major policy shift that accompanied the transfer of power to the Obama administration in 2009. Considering that the scenes of torture early in the film take place under the Bush administration's tenure, the prevailing view that waterboarding and other coercive means were being employed according to the Bush-Cheney-Rumsfield world view are entirely justified, especially as conflicting accounts concerning the CIA's interrogation methods during this period obscure the facts. Zero Dark Thirty even makes it clear that the coercive means of interrogation ceased with the incoming Obama administration in 2009.

With so many of the details regarding the interrogation of captured Al Qaeda operatives and their associates and the role in the search for bin Laden being hazy at best, it is the public and the media that now face the responsibility of describing the film correctly. Which means we would do well by calling Zero Dark Thirty NOT a docudrama, but a specudrama, insofar as so many of the lacunae in the information released to the public by the Obama administration, the CIA, and the Senate Intelligence Committee has been filled in by Bigelow and Boal as it should have been in a fictional account written amid a smokescreen of disinformation and denial surrounding the means by which American intelligence ascertained where bin Laden was hiding. We should remember that the film's interrogation scenes are no more than a means to an end. The film is, after all, about the alleged assassination of bin Laden.

No doubt you have noticed that I have repeatedly used the words "alleged bagging" and "alleged assassination" of bin Laden. I do so not because I imagine there to be some conspiracy in falsifying the identification of bin Laden's body, but because there has been virtually no scrutiny by the media of the Obama administration and the CIA over the disposal of bid Laden's body at sea without allowing representatives of the public to view the individual shot and seized by Navy Seals. It has always struck me as unusually credulous of the media, of Americans, and of the various heads of state and governments around the world, to have accepted the death of Osama bin Laden on no more than the word of a few dozen or so witnesses to his demise, most of whom remain shadowy figures to the public--and with so little dissent over the absence of proof (DNA, body weight and height, physical resemblance, identification by bin Laden's "wife," etc.) presented in detail and debated before the public.

For this writer, such a void in evidence and debate coupled with so generous a credulity on the part of the global media and their audiences makes for the far bigger controversy contained in the film--a controversy potentially far bigger than the accuracy of scenes concerning the waterboarding and dog-leashing of detainees. At least for this viewer, the real accomplishment of the film is the ambiguity with which Bigelow and Boal surround bin Laden's assassination and the transport of his corpse. Instead of alluding to the domestic and international conferences that the Obama administration orchestrated to decide on how to dispose of bin Laden's body once they were satisfied it was properly identified, Bigelow and Boal underline the disproportion between the evidence of bin Laden's death and the credulity of the global audience by refusing us anything but the most oblique view of bin Laden's corpse.

This too is in keeping with the prerogatives of fiction writing, but in this case the reflection of blatant uncertainty greeted with unwarranted yet widespread credulity casts a long shadow on the real history that transpired on May 2, 2011. The darkness implied by Bigelow and Boal's film title in this instance is more than another Hollywood infatuation with the ominous and existential chiaroscuro of the mind. More even than the cinematic shadows that keep special effects both within studio budgets and appearing believable onscreen. The darkness of political and security interest keeps an international audience from demanding more proof of bin Laden's death, while the world-likeability of Barak Obama suspends disbelief in the manner that is frequently accorded charismatic leaders, even when it is to our own disadvantage. In this light, Bigelow and Boal have made clear the contrast between how badly people within the government and its intelligence wanted bin Laden found, yet never made it clear over the decade of his manhunt whether they preferred procuring his corpse over his testimony. Bigelow and Boal wisely offer us no clear explanation as to why bin Laden ended up dead, while making it eminently clear that they believe the Navy Seals did anything but bungle the mission in killing bin Laden. Yet the wide berth they gave to ambiguity in the final scenes of the death and identification of bin Laden at the same time leaves open much room for doubt both over whether the Al Qaeda leader could have been brought back alive and whether his corpse had been properly identified with every means available.

Let me state that I am to be counted among those who believe that Navy Seals did kill bin Laden on May 2, 2011 in Abbottabad. But I believe not out of some benign generosity of trust in my government--which has been known before to misinform its citizens during wartime in the name of national security. I believe because I, like so many Americans, want the entire episode of 9/11 and our demand for retribution for the lives of the nearly 3,000 Americans lost to come to a quick and final culmination. How else are we as a nation to move forward after twelve years? To leave Afghanistan in good conscience? To initiate and carry on negotiations with our former foes? The problem is that uncertainties linger even when they seem not to, and such uncertainties left unstated in the public consciousness over whether or not it was bin Laden who died in Abbottabad, risks growing septic in the body politic both at home and abroad--especially as Al Qaeda would likely flourish with any false corroboration of bin Laden's demise.

It is unlikely that any serious discussion will ensue regarding the filmmakers' ambiguous handling of the final scenes so long as the film remains a lightning rod for criticism over its early depictions of CIA torture of Al Qaeda detainees. It is also arguable that Bigelow and Boal have considered that the public's easy trust in a CIA adumbration deserves to be drawn out with calculated ambiguity at the film's conclusion. This seems even more relevant as we evaluate how much Zero Dark Thirty will effect the popular view of American and World History. And that is even more reason why we in the media should be concerned with buttressing the fact that Zero Dark Thirty remains but one director's and one writer's admitted speculation inserted into the history books for so long as the facts of the hunt for bin Laden remain classified. Instead of asking questions about why American Navy Seals assassinated bin Laden, we are getting bogged down with an argument of what should and shouldn't have been filmed, which is never an argument meant to be resolved by anyone other than the artists concerned.

No doubt the critics in opposition to the film's scenes of torture see themselves as legitimately pointing out the best direction for an art form, a work of fiction, to take. They are suggesting that there is a decidedly right way and a wrong way to aim a fictional lens at the facts, even when those facts are dispensed unevenly by deeply interested authorities.

The problem with such a narrow view of the facts is that critics such as Mayer, Bergen and Gibney aren't considering their own paternal overreach. At least it is overreach so long as the facts surrounding the Bush administration's interrogations cannot be made public and the authorities themselves remain divided over what is the best means of deriving information from captured enemies. Besides that the moral high ground doesn't always make for the best art today, there is the irrefutable question of how two moral high grounds can be climbed in one film without both being diminished in the condensation required to fit them.

Zero Dark Thirty cannot be both about the hunt for bin Laden AND the argument for a humane interrogation of enemy detainees. The scope of two such issues competing for screen time is simply too great for one film and the loss of clarity that would ensue would strangulate the story. Gibney knows this--he states as much at the outset of his article. The fact is, Zero Dark Thirty is not a story about the kind of moral certitudes that George Bernard Shaw (or Gibney) would have levitated. As in The Hurt Locker, the team of Bigelow and Boal excel in flying a filmcraft of moral and cognitive relativism--one made more exciting by the dynamic tension of uncertainties elaborated for a global audience holding diverse ideological viewpoints, not the kind of social, moral and political imperatives that George Bernard Shaw sought to exalt his Socialist world vision--the same imperatives that withered under the Socialist regimes that attained power and denounced the freedom of artists in favor of state-dictated aesthetics and content.

That's not to say that Zero Dark Thirty is without moral and political implications. It is filled with them at every step and turn--including the scenes of waterboarding and other coercive methods of interrogation. What the filmmakers decline to do--yet what their critics demand of them--is deduce for the viewer what the final judgments regarding torture should be. Instead, Bigelow and Boal allow us the room to make our own inferences as to what is right and wrong. The end product will inevitably be a variance of opinions that put the judgements of its audience at odds with one another. But that is what the art of democracies are supposed to do--allow us our diverse opinions even when they lead to discord. And that is the reason that both The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty avoid the pitfalls of propaganda that the film's critics and the Senate Intelligence Committee seem to be calling for.

The critics of Zero Dark Thirty's torture scenes, both those liberals who find such scenes witholding moral criticism and those conservatives who find them deficit of the patriotism that in their eyes justifies and perpetuates torture, would have the filmmakers filter, even direct, their audience's views. Anyone who sees Bigelow and Boal's refusal to make their film a denunciation of torture to be tantamount to caving in to either Senatorial grandstanding or the Hollywood bottom line would benefit by remembering that we cannot as liberals defend an art that makes our ethical and political decisions for us without opening the door of art and entertainment to the manipulations of all manner of control, including those engineered in the name of fascism.

Bigelow in 2009 went on record in an interview with The New York Times' Manohla Dargis concerning her aim as a filmmaker of exposing how "fascism is very insidious, we reproduce it all the time," not merely on the extreme Right or Left. It is Bigelow's curtailment of her own manipulative impulses that resonates with the restraint that we read throughout Zero Dark Thirty. In this viewer's opinion, it is such vigilance against audience manipulation that both keeps Bigelow's films buoyantly above the majority of Hollywood productions and excuses her lapses from the so-called facts concerning the CIA's use of torture, especially given that the facts were by and large not presented to the film's writer and director to begin with.

To answer Jane Mayer's question posed in The New Yorker, "Can torture really be turned into morally neutral entertainment?" My answer is, there is no morally neutral entertainment. But there is entertainment that allows the intelligence of the viewer to work out his and her own moral dilemmas concerning how we are to respond to the scenes streaming before us.

Dear directors and screen writers, critics and senators. Trust us. That is, trust we who are your audience, we who can think for ourselves. It is WE--not the critics, not the government, especially not those who would shape our opinions for us--who determine what is credible (and a hit) and what is not.

Read other posts by G. Roger Denson on Huffington Post in the archive.

Follow G. Roger Denson on Facebook and Twitter.

?

?

?

Follow G. Roger Denson on Twitter: www.twitter.com/GRogerDenson

"; var coords = [-5, -72]; // display fb-bubble FloatingPrompt.embed(this, html, undefined, 'top', {fp_intersects:1, timeout_remove:2000,ignore_arrow: true, width:236, add_xy:coords, class_name: 'clear-overlay'}); });

Source: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/g-roger-denson/zero-dark-thirty-defendin_b_2357702.html

ovechkin one world trade center bks new dark knight rises trailer khloe and lamar oklahoma city thunder rajon rondo

LAS CRUCES ? The New Mexico State Aggie football team entered the year with high expectations: After an improved 2011 season, the hope was the team could take a similar step forward and challenge for its first bowl game since 1960.

LAS CRUCES ? The New Mexico State Aggie football team entered the year with high expectations: After an improved 2011 season, the hope was the team could take a similar step forward and challenge for its first bowl game since 1960.

A private investigator named Paul Huebl claims that singer Whitney Houston was murdered by drug dealers and has a new surveillance video to prove it! Huebl says he has turned over evidence to the FBI that shows the 48-year-old singer was killed over owing a whopping $1.5 million to drug dealers. The medical examiner ruled ...

A private investigator named Paul Huebl claims that singer Whitney Houston was murdered by drug dealers and has a new surveillance video to prove it! Huebl says he has turned over evidence to the FBI that shows the 48-year-old singer was killed over owing a whopping $1.5 million to drug dealers. The medical examiner ruled ...